URL: https://www.desy.de/news/news_search/index_eng.html

Breadcrumb Navigation

DESY News: The most precise picture of the proton

News

News from the DESY research centre

The most precise picture of the proton

After 15 years of measurement and another eight years of scrutinizing and calculation, the particle physics collaborations H1 and ZEUS have published the most precise results about the innermost structure and behaviour of the proton. The two experiments which took data at DESY´s particle accelerator HERA from 1992 to 2007 have combined their data of over a billion collisions of protons with electrons or positrons, antiparticles of the electrons. About 300 authors of 70 institutions have contributed to the analysis.

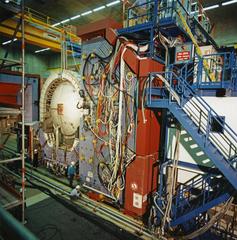

The HERA accelerator at DESY in Hamburg was unique in that it smashed two totally different kinds of particles into each other – protons and electrons or positrons. HERA thus consists of two different accelerator rings: a superconducting proton ring (top) and a normal-conducting electron ring (bottom). HERA ran from 1990 to 2007.

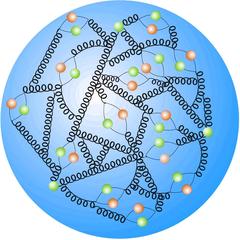

Protons are in the core of each single atomic nucleus in the universe. Their composition of three quarks – two up and one down quark – which are held together by so-called gluons, carrier particles of the strong force, is well known since decades and taught in schools. However, the real picture of the proton is much more complicated: the proton is a sizzling soup where gluons can produce more gluons and can also split into pairs of quarks and antiquarks – the so-called sea quarks – all of them interacting again very quickly.

HERA's scientific legacy: the proton does not only consist of three quarks (green) being held together by gluons (springs), but is a sizzling place of gluons and pairs of quarks and antiquarks (orange) interacting with each other.

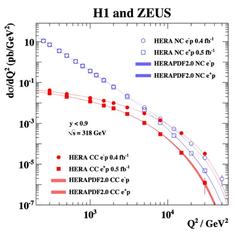

As one of the results, the two experiments measured the probability for several behaviours of these lepton-proton scattering processes and confronted the results with the best understanding of the proton substructure, a theory called quantum chromodynamics (QCD). The HERA results confirmed perfectly the QCD theory, showing that the apparent structure of the proton becomes more dynamic with increasing energy at which the proton is probed.

The H1 detector recorded about a billion collisions from 1992 bis 2007.

The ZEUS detector, here shown opened for maintenance, weighed 3600 tons and was about 20 metres long

“Through the combination of the measurements of the two experiments we achieve the highest possible precision,” says Stefan Schmitt (DESY), H1 spokesperson. “The combined data set benefits not only from increased statistics, but also from an improved understanding of each separate measurement and from an inter-calibration that occurs because the two collaborations employ different detectors and experimental techniques in their measurements.” But combining data of different particle detectors analysed by different techniques and collected over 15 years is a mammoth task. “Each of the data points has up to 20 sources of uncertainty, and in the combination of the data, each of the 20 sources may be correlated with the uncertainties of the next data point and all of these correlations need to be understood,” says Matthew Wing (University College London), spokesperson of ZEUS.

Already in 2009, the two collaborations published a joint paper on the structure of the proton, but only based on the data of the first HERA run till 2000. With 600 citations till today, it is already one of the most cited papers in the field. The recent publication is based on the fourfold amount of particle collisions and also contains data from special runs at different particle energies.

However, there is some mystery left in testing the Standard Model of particle physics. “Especially at a low energy transfer between electron and proton, the reference theory of quantum chromodynamics used cannot sufficiently describe our measurements,” says Wing. “This will definitely be something where theorists and phenomenologists will keep an eye on in the future.”